Eduardo Marisca | 10 Jan 2016

I’ve become one of those people who listen to music from vinyl records.

It all started a few months ago, when I was visiting The Strand bookstore in New York and bumped into their record section in the basement. I thought it very quirky and hipster of them, and started flipping through their selection. Lots of interesting records I’d listened to before and that I knew I’d have no trouble finding online, just by pulling up Spotify on my phone right there. Put it simply: I just didn’t get it.

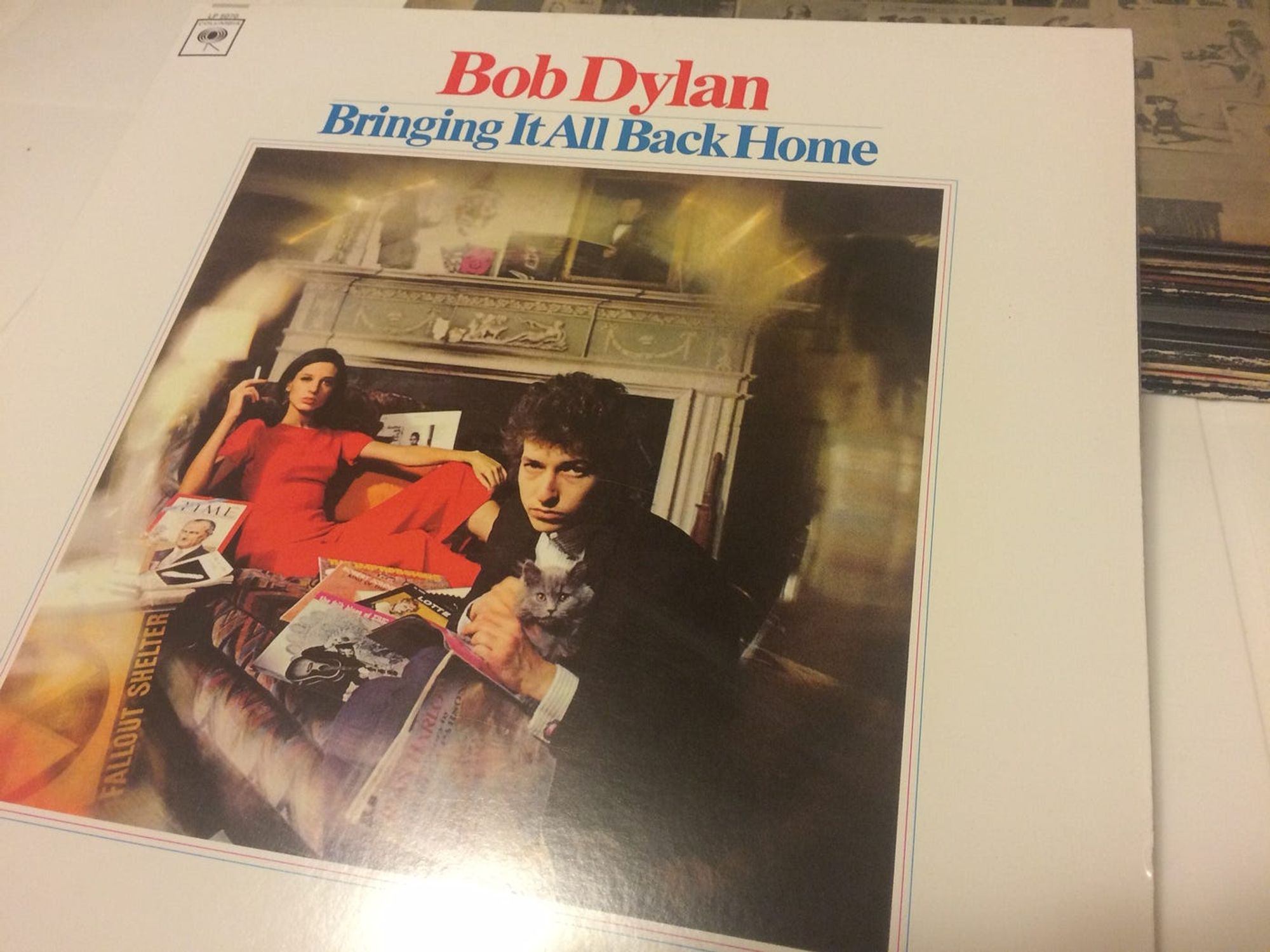

But then I stumbled upon something special: Bob Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home, a 1965 album interesting to me primarily because it is one of Dylan’s key moments of reinvention. In this album, Dylan is struggling to leave behind his identity as a protest and folk singer, and figuring out what it means to embrace an identity as a performer closer to rock. The album is still in-between both worlds (his following album, Highway 61 Revisited, would push him more decidedly in an electric rock direction) and it swings in-between definitions as well. The album is a great reminder of how hard it is to choose to reinvent yourself, even more so when you’re at the top of your game and there are so many eyes and expectations on you to be and act in a specific way.

I love this album, and I’ve listened to it dozens of times beginning to end. Every time I had done so, it had been as a series of MP3 files that existed within my hard drive. But now I was holding it, just as it had originally been intended to exist in the world.

It didn’t make much sense at the time, but I decided I wanted it. I had no record player back home, so really no way to listen to it, but I went ahead and got it anyway. I was happy to own the object itself as a totem or a prop.

Back home after a few days, I set out one weekend to find a record player. I wasn’t looking for anything particularly fancy or elaborate — I actually wanted to spend as little as possible on hardware. After a little bit of walking around, I found a cheap player for $40 at an electronics store which was great because it had built-in speakers (meaning I wouldn’t have to concern myself with finding an amplifier or additional speakers). I came back home, set it up, and started playing my new Dylan record.

It sounded pretty bad, to be quite honest.

But that was fine. What followed was a super interesting experience made possible by the very technical shortcomings we consider to have overcome in newer forms of media. For starters, the sound quality wasn’t great — without an amp or external speakers, it wasn’t exactly a hi-fi setup. There was no easy way to skip forwards or backwards through the album, so I basically just had to sit and listen through it. And 20 minutes in, I had to physically flip over the record to listen to the second half if I wanted to keep hearing anything. So I basically had to stay close to the player the entire time, waiting for the moment when I’d have to flip over the record. I sat on the floor next to the player for about 20 minutes, carefully flipped over to the other side, and then just sat there for another 20 minutes until it was done.

When I started thinking about it, I realised this had been my first time listening to music as a primary activity in many, many years. For about 40 minutes, I had done nothing else other than listening to this album.

You see, nowadays we probably listen to more music than in any previous time. We listen to music all the time — at home, on our phones, in the car, at bars and restaurants, at shopping malls and stores, music is just there all around us, all the time. But it is almost always happening as a background activity to something else, as a way of carrying a soundtrack to entertain us while we run errands, while we work or while we hang out with friends. We’ve so mastered and integrated music that we rarely have to think about it. We set up a few playlists or radio stations, mark a few songs and artists as favourites, and then just let algorithms and wireless communications protocols handle the rest.

And don’t get me wrong, that’s awesome — I love being able to carry around infinite music in my pocket, plug in some good headphones and then doze off to a cool soundtrack during a long flight. This is all very practical and it’s a great way to enjoy music. But my discovery of vinyl was just a reminder that there were also other ways to do it — ways that are closer to going to a concert, where you’re intentionally going for the music and paying attention intently, than to watching television, where the content often fades into the background and keeps you company. And this other way to do it brought up different affordances and qualities in the medium and the content.

I’m not a purist, and it’s not like I’m now listening to all of my music on my record players and I’ve forgone my Spotify account. Far from it. But vinyl has affected my musical behaviour. Now, every time I travel I notice and walk into record stores, and start flipping through their selection for a little bit. Often I run into one thing or another that’s interesting, and usually very cheap. But I’ve also found that I’m most often purchasing records that I’ve already listened to in the past, either as CDs or as MP3s, and I’m familiar with. Records are to me more about reconnecting with meaningful memories in a tangible way, where there’s an object I can hold, examine, contemplate, and collect. These objects then fall into a ritual practice of actually playing them, usually during otherwise empty Saturday and Sunday afternoons. It takes barely any effort to play a track off Spotify; conversely, it takes a lot of intention and commitment to play a record. You have to decide it, and you have to want it. And because it’s almost like a commitment, you sit through and you pay attention.

I’ve found that I’m paying attention to new things — especially record stores, which I’ve discovered are plentiful in Lima if you dig around long and deep enough. It’s fascinating how people connect over records: shop owners are very serious and intentional about their selections, and they’ll boast and feel proud about new arrivals and recent finds they’ve just added. They also tend to be extremely helpful, pointing in the right direction for genres they’re not specialised in, or support regarding audio hardware and gear. I tried to spend as little as possible getting my record player, but now I’m increasingly interested in getting a good-quality amplifier and a good set of speakers so I can set up myself with a decent listening situation.

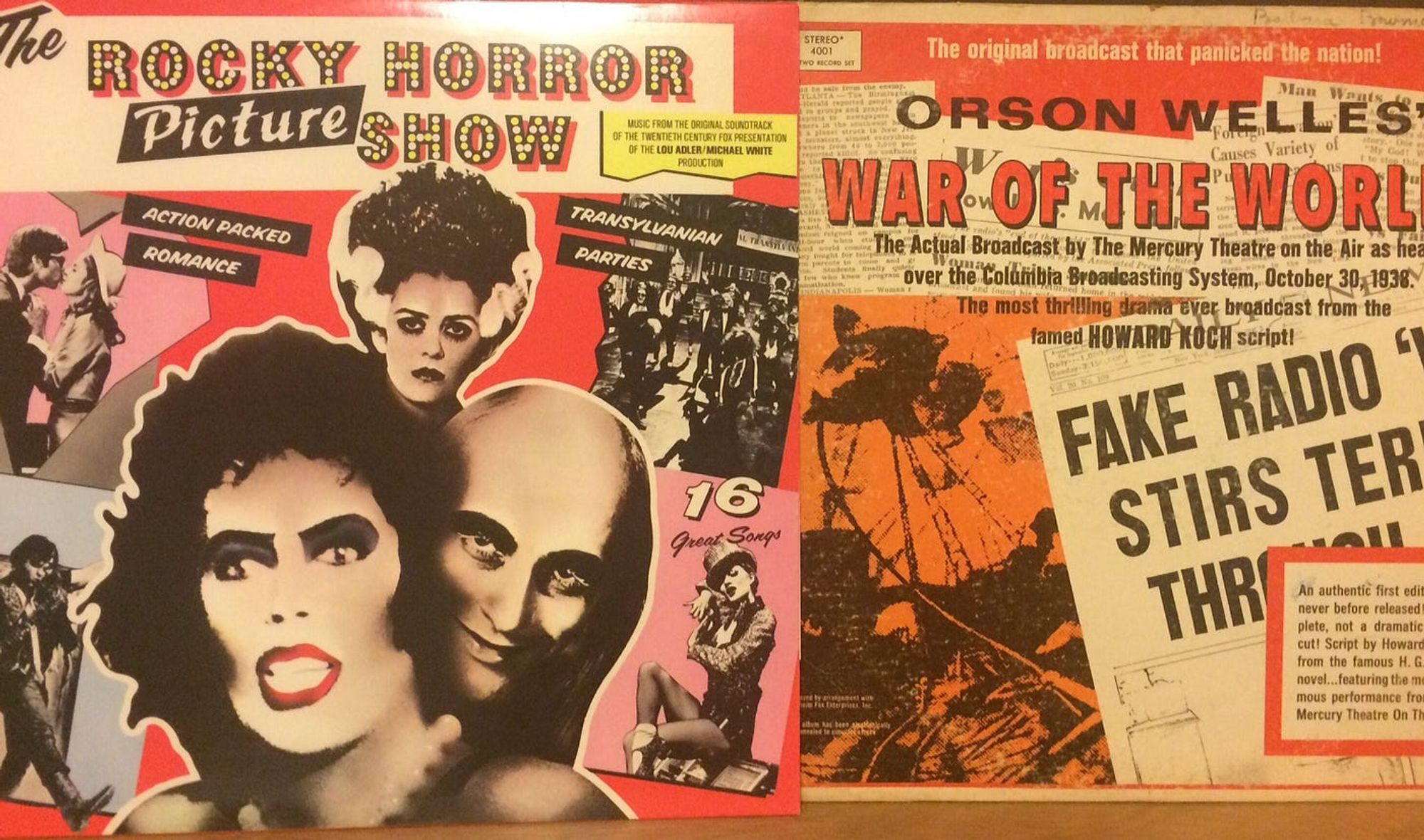

And then I’m finding the objects themselves, the records, to be incredibly interesting. I’ve had shop owners try to persuade me to get a record simply because of its historical value, as a collectible, or even as a decorative piece. “That’d be a great thing to have around for people to see,” I’ve been told. There’s some really interesting pieces you can find, and some things I’ve just gotten because it felt like an interesting piece to own. A couple months ago, I found the soundtrack to The Rocky Horror Picture Show at a local shop. And just last week, I found a vinyl recording of the original radio broadcast for Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds at a record store in Pittsburgh — which was actually the back room to a guy’s woodworking shop, open to the public for a few hours on the first Friday of every month. This is probably something that for practical purposes would be much easier to find online. But having it as a physical record imbues it with a strange sense of permanence, creating this opportunity of owning this tiny bit of media history.

There’s a strange ethos around listening to music on vinyl records, one that can easily become a sense of smugness or snobbery around music and audio. Yes, there’s a lot of people who really just love music, but also a non-trivial number of people who enjoy pontificating about why one specific obscure recording is better than another, or why your musical tastes are uninformed and shallow. But I guess so it can be with most things, really. What I’ve come to really appreciate is how I can now choose to experience recorded music in a different way. Every so often, I’ll make myself a cup of coffee and put on any of my favourite records for a while, then just lie on the floor for a little bit while I listen to it. After a few minutes I’ll flip it over and listen to it some more, and then repeat with two or three albums. It’s like choosing to read for a little bit, or to watch a movie: it’s choosing to spend a prolonged amount of time in the company of some music. Similarly, shopping for records is like browsing for books: you walk into a store without looking for anything in particular, and the entire value of the transaction is based on what you might stumble upon.

The reason why this has become meaningful to me is just because it is so exceptional. During most of the week, I’m running around super busy, and during the evenings I’m either too tired or too busy. Even weekends tend to be busy affairs, running errands, shopping around for things, or hanging out with people. To be able to choose to spend 40 minutes just listening to music is an immense exception, a privilege that then becomes so much more valuable.

Maybe then it’s not even about the music. It’s about time travel. The time spent next to the record player, filled with nothing but a little bit of music, is just a complex existential negotiation with time. It’s about choices, and the options we’re provided to decide how we best spend our time.

It’s an act of resistance against entropy, however unsuccessful it might ultimately turn out to be.